Ciguatera in Canary Islands.

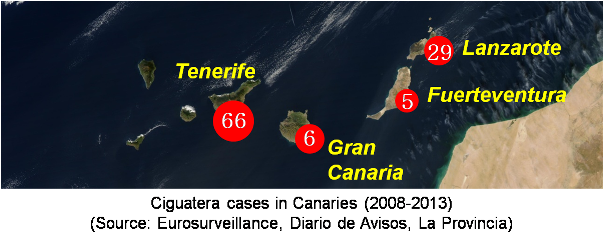

First registered case of ciguatera was reported in 2004 due to amberjack consumption (Pérez-Arellano et al 2005) and later in 2008 new intoxication episodes were detected. From that year on ciguatera reports have occurred each year (Matute et al. 2009; Boada et al. 2010; Núñez D. et al. 2012). Up to year 2013 there have been officially 100 people affected by ciguatera in the archipelago, all of them due to amberjack (Seriola spp.).

However, in December 2013 local news (eg. La Voz de Lanzarote, 12/12/2013) referred to a new intoxication (10 people) after consumption of dusky grouper (Ephinephelus marginatus). Some of these ciguatera cases were due to fish from local markets but most others from sport fishing.

The origin of ciguatera in Canary Islands, as in other parts of the world, are benthic dinoflagellates of the genus Gambierdiscus. It is well documented the presence of these microalgae in Tenerife, La Palma, La Gomera and Gran Canaria (Fraga et al 2011; Fraga and Rodríguez, 2014) but not their temporal and spatial distribution throughout the archipelago. This genus was recently reported in Madeira Is. (Kauffaman and Böhm-Beck, 2013) and cases of ciguatera in the Savage Islands, between Madeira and Tenerife, were recorded. In the African coast, it was found Gambierdiscus off the coast of Morocco and also in Cape Verde Islands (Silva, 1956; Ennaffah and Chaira, 2014). The source itself for ciguatera in Canaries (local or neighbour areas in Macaronesia), remains to be discovered and there could exist several vectors.

There are no scientific evidences yet about origins and vectors of ciguatera illness transmission in the Canaries. Some technical reports elaborated in the region suggested a number of species that may act as potential vectors based on their eating habits (herbivores or omnivores). These species would accumulate toxins in their diet and transmit them to their predators (amberjack, grouper, abbots, barracuda, wahoo, etc.).

Some of these potential vectors for ciguatera could be the following:

BOGUE (Boops boops)

Habitat: Pelagic or benthopelagic, over all seabed habitats, from the surface to 250 m depth; juveniles are observed sometimes in large tidal pools.

Biology: Form numerous shoals that in coastal waters usually concentrate mainly in the vicinity of veriles and lows. They initially consume zooplankton, but also other omnivorous species of benthic invertebrates, algae (mainly in adults) and fish eggs.

SADDLED SEABREAM (Oblada melanura)

Habitat: benthopelagic, all seabeds, from the shore to 35 m depth, usually swimming in midwaters.

Biology: usually forming schools, sometimes very numerous. It is an omnivorous species that feeds both on planktonic invertebrates and other fish spawning like small fish (gueldes), benthic invertebrates and algae.

SALEMA (Sarpa salpa)

Habitat: Demersal coastal habitats, from shore to 50 m depth, on rocky, rocky-sandy bottoms (also in sebadales or patches) covered by seaweeds.

Biology: gregarious, can form very numerous shoals. The adult specimens are almost exclusively herbivorous.

CANARY DAMSEL (Abudefduf luridus)

Habitat: demersal, on rocky, rocky-sandy bottom, from the shore (including large tidal pools) up to 50 m depth.

Biology: gregarious, although strictly speaking they do not form shoals. It is usually found on the seabed or a few meters above it. The diet is omnivorous but with a high degree of herbivory, mainly eating seaweed and small invertebrates associated to them.

PARROTFISH (Sparisoma cretense)

Habitat: demersal, rocky, rocky-sandy bottom, from the shore to 100 m depth, but mainly above 50 m; youth are also in Sebadales or patches.

Biology: They have a great tendency to form schools of numerous examples (“jets”), especially during the summer, but can also be found alone or in pairs. With its powerful teeth torn pieces of turf and calcareous algae, along with invertebrates that are in them, they are their main food.

BERMUDA SEA CHUB (Kyphosus sectatrix)

Habitat: benthopelagic, rocky, rocky-sandy bottom, from breaking areas up to 50 m depth. It can be found in oceanic waters under floating objects.

Biology: gregarious, it develops many schools, especially in very steep seabeds. It is basically a herbivorous species, but also consumes small crustaceans and mollusks.

ORNATE WRASSE (Thalassoma pavo)

Habitat: Demersal rocky, rocky-sandy bottoms from the intertidal pools up to 250 m depth; especially abundant in shallow waters covered by algae.

Biology: It prefers shoals with numerous individuals and feeds on various benthic microinvertebrates (mollusks, crustaceans, polychaetes, etc.).

WHITE TREVALLY (Pseudocaranx dentex)

Author: Carvalho Filho, A. (FISHBASE)

Habitat: Benthopelagic coastline, over rocky, rocky-sandy bottoms, from shore to 100 m deep.

Biology: Although it may be found alone or in small groups, shows a tendency to form schools of numerous copies. Often actively swimmer a few meters above the bottom, reaching close to the surface, but it is not uncommon to see large specimens in the shelter of caves and ledges. The diet is based almost exclusively on benthic invertebrates, which get rummaging over the seafloor (Falcón et al. 2009).

Monitoring and prevention of ciguatera in Canaries.

In 2009, health authorities established control over the potentially ciguatoxic fish species before its selling in local markets. A first method used for detecting ciguatera – called CiguaCheck -, was ineffective and rendered unacceptable rates of false positive and negative results, so it is no longer in use and has been replaced by cytotoxicity assays. At present, the government of the Canary Islands (through the Directorate General of Public Health of the Canary Islands Health Service), has established a System of Epidemiological Surveillance of ciguatera poisoning in the Canary Islands. This system is aimed to collect all the relevant information on the ciguatera cases that arrive to the public health services, in order to determine the incidence and epidemiology of submission of such poisoning.

The protocol and survey form to report possible cases of ciguatera are available on the website of the Canary Islands Health Service (http://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/sanidad/scs/contenidoGenerico.jsp?idDocument=bb1799ed-b4c0-11de-ae50-15aa3b9230b7&idCarpeta=b0821886-6aee-11de-b75e-bbb3e7dd3aa4)

On the other hand, the Regional Ministry of Fisheries and Water of the Canary Islands has implemented a “Protocol of action in the Plan for determining Ciguatera Toxin presence in the Canary Islands”. In this regard, the minimum weights over which fish individuals must be analysed for the presence of ciguatoxins are the following:

| Common name | Species | Weight |

| Amberjacks | Seriola dumerili | > 15 kg |

| Seriola carpenteri | ||

| Seriola fasciata | ||

| Seriola rivoliana | ||

| Wahoo | Acanthocybium solandri | > 20 kg |

| Bluefish | Pomatomus saltatrix | > 9 kg |

| Island grouper | Mycteroperca fusca | >7 kg |

| Groupers | Ephinephelus spp. | > 22 kg |

| Blue marlin | Makaira nigricans | > 130 kg |

| Atlantic bonito | Sarda sarda | > 8 kg |

| Swordfish | Xiphias gladius | >110 kg |

Ciguatera in the media:

2013 http://www.lavozdelanzarote.com/articulo/sucesos/nuevo-brote-ciguatera-lanzarote-menos-diez-personas-intoxicadas/20131212151153085323.html http://elperiodicodelanzarote.com/lanzarote/sucesos/4657-al-menos-tres-personas-envenenadas-por-ciguatera-al-comer-pescado-en-tres-restaurantes-de-lanzarote.html http://www.diariodeavisos.com/2013/02/descontrol-pesca-deportiva-impide-frenar-brotes-ciguatera-en-canarias/

2012 http://noticias.lainformacion.com/salud/enfermedades/16-casos-de-intoxicacion-por-ingesta-de-medregal-con-ciguatera_DDuiohL4sk2p4LPECbomF4/ http://www.abc.es/20120608/sociedad/abci-brote-ciguatera-canarias-201206080954.html

2011 http://www.canarias7.es/articulo.cfm?Id=224562

More information…

COI de UNESCO: http://hab.ioc-unesco.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=47:ciguatera&catid=29:activities

FAO: http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5486e/y5486e0q.htm

National Institute of Health USA: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/spanish/ency/article/002851.htm

Eurosurveillance: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20188

Ciguatera online (Institute Louis Malardé): http://www.ciguatera-online.com/index.php/en/

Bibliography

Boada LD, Zumbado M, Luzardo OP, Almeida-González M, Plakas SM, Granade HR, et al. Ciguatera fish poisoning on the West Africa Coast: An emerging risk in the Canary Islands (Spain). Toxicon. 2010;56(8):1516-9.

Ennafah B, Chaira K. First report of Gambierdiscus in Moroccan Atlantic Waters. Harmful Algal News 2014; 50:20.

Fraga S, Rodríguez F, Caillaud A, Diogene J, Raho N, Zapata M. Gambierdiscus excentricus sp nov (Dinophyceae), a benthic toxic dinoflagellate from the Canary Islands (NE Atlantic Ocean). Harmful Algae 2011; 11:10-22.

Fraga, S., Rodríguez, F. (2014). Genus Gambierdiscus in the Canary Islands (NE Atlantic Ocean) with description of Gambierdiscus silvae sp. nov. A new potentially toxic epiphytic benthic dinoflagellate. Protist. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2014.09.003

Matute P, Núñez D, Abadía N. Caracterización de dos brotes autóctonos de intoxicación alimentaria por ciguatera ocurridos en Tenerife en noviembre de 2008 y enero de 2009 [Characterisation of two indigenous outbreaks of ciguatera food poisoning which occurred in Tenerife in November 2008 and January 2009]. XXXVII Reunión de la Sociedad Española de Epidemiología; 2009 Oct 28-30; Zaragoza, Spain.

Núñez D, Matute P, Garcia A, García P, Abadía A. Outbreak of ciguatera food poisoning by consumption of amberjack (Seriola spp.) in the Canary Islands, May 2012. Eurosurveillance, Volume 17, Issue 23, 2012.

Pérez-Arellano, J.L., Luzardo, O.P., Brito, A.P., Hernández Cabrera, M., Zumbado, M., Carranza, C., Angel Moreno, A., Boada, L.D., 2005. Ciguatera fish poisoning Canary Islands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11 (12), 1981–1982.

Silva ES. Contribution a L’étude du microplancton de Dakar et des régions maritimes voisines. Bulletin de L’I.F.A.N. XVIII, série A. 1956; T.XVIII, sér. A, nº 2:335-371.